Does Cows With a Gentic Defect Make Th Beef Taste Bad?

The cows in Farmer John's pasture lead an idyllic life. They roam through tree-shaded meadows, violent upwardly mouthfuls of clover while nursing their calves in tranquility. Tawny brown, compact and muscular, they are Limousins, a breed known for the quality of its meat and much sought-after by the high-end restaurants and butchers in the nearby food mecca of Maastricht, in the southernmost province of the Netherlands. In a year or two, meat from these dozen cows could end up on the plates of Maastricht's better-known restaurants, but the cows themselves are not headed for the butchery. Instead, every few months, a veterinarian equipped with fiddling more than a topical anesthetic and a scalpel will remove a peppercorn-size sample of muscle from their flanks, run up upwards the tiny incision and transport the cows back to their pasture.

Limousin cows in Farmer John's pasture. Mosa Meat will cultivate their cells in a lab to abound into hamburger that is genetically identical, no slaughter required

Ricardo Cases for Fourth dimension

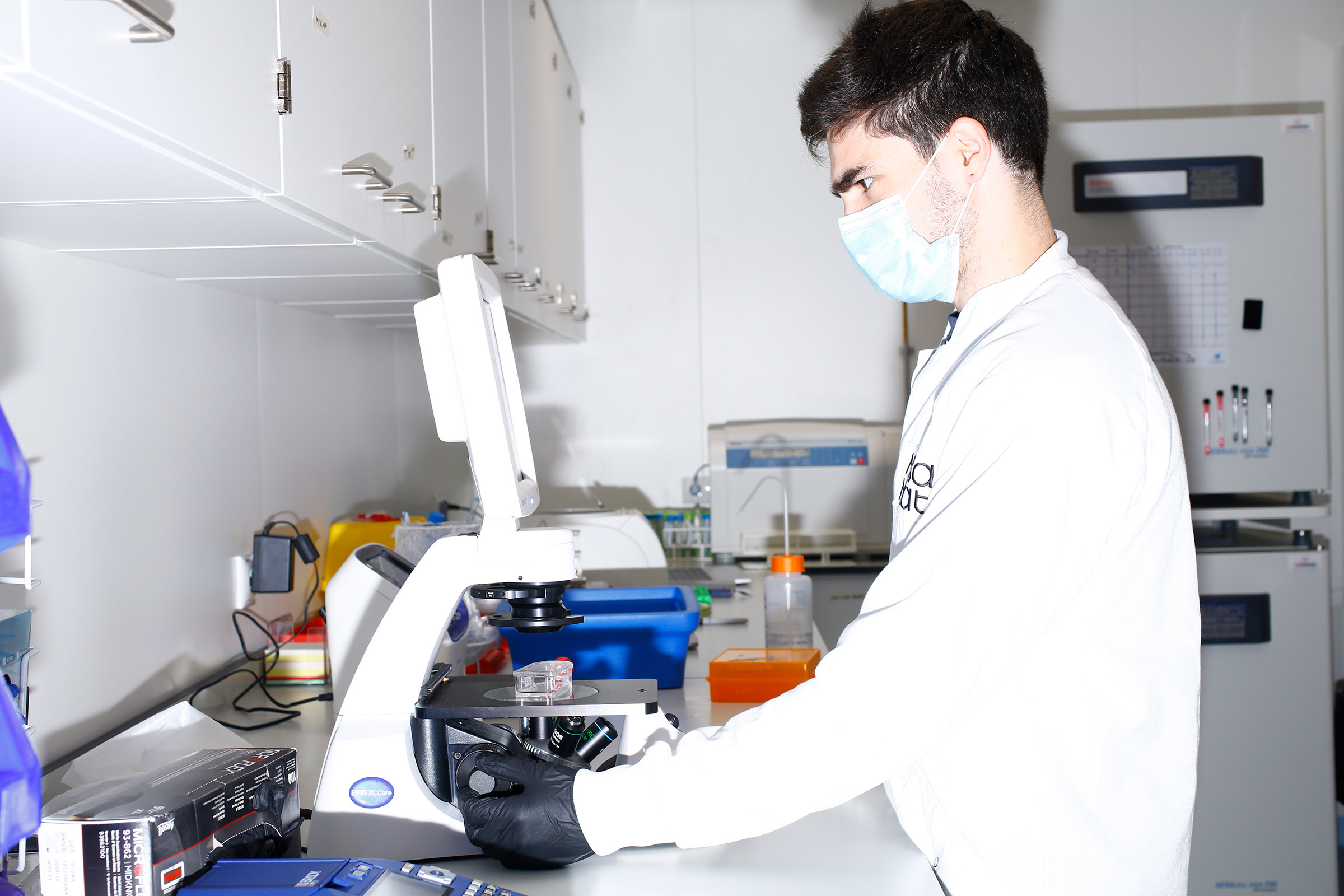

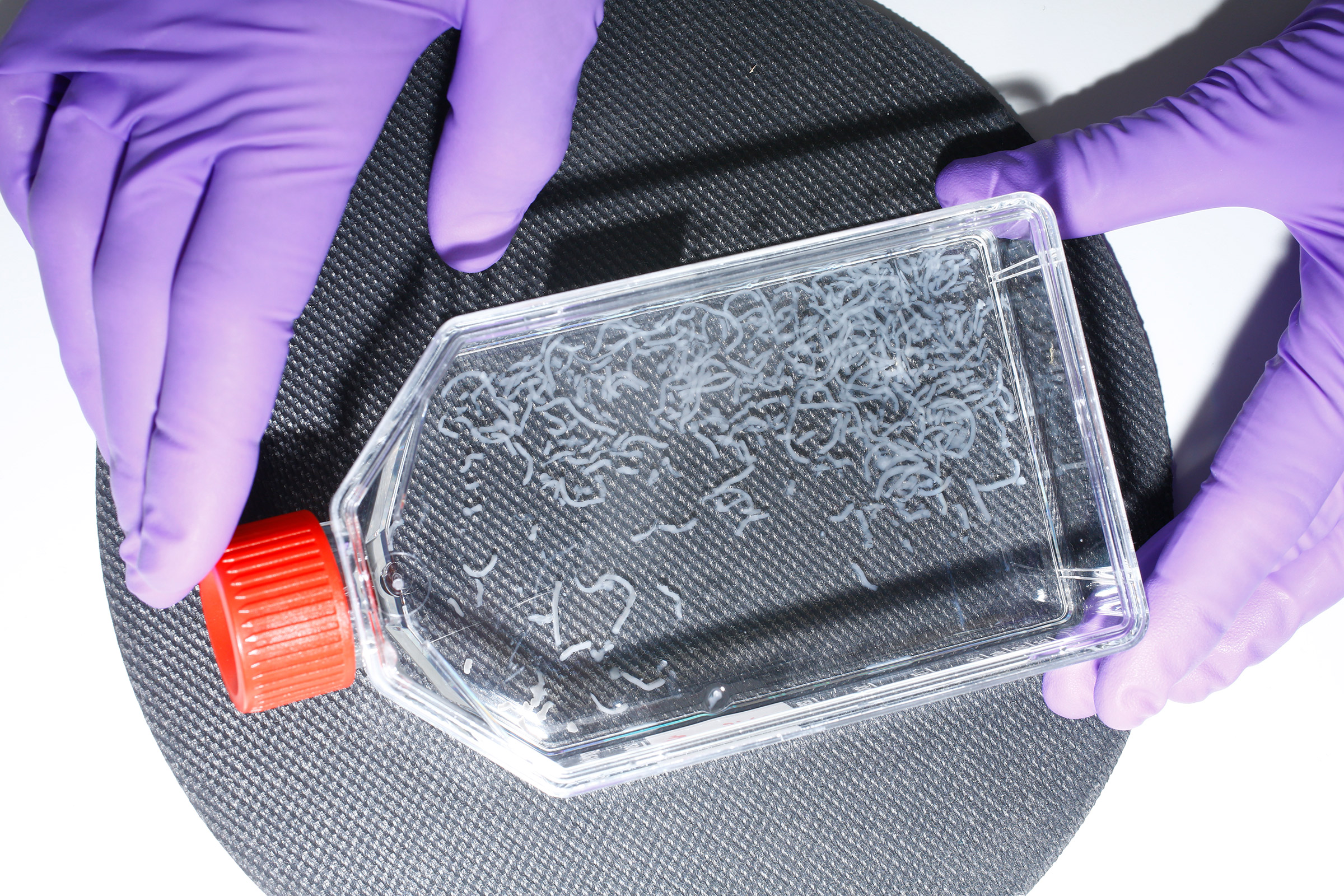

The biopsies, meanwhile, will be dropped off at a lab in a nondescript warehouse in Maastricht's industrial quarter, v miles away, where, when I visit in July, cellular biologist Johanna Melke is already working on samples sent in a few days prior. She swirls a flask total of a clear liquid flecked with white filaments—stem cells isolated from the biopsy and fed on a nutrient-dense growth medium. In a few days, the filaments will thicken into tubes that look something like brusk strands of spaghetti. "This is fat," says Melke proudly. "Fat is really important. Without fat, meat doesn't taste equally skillful."

Mosa Meat has recruited a global team of lab technicians and biologists to develop, build and run its scaled-up operations. Rui Hueber, checks the wellness of contempo prison cell samples.

Ricardo Cases for TIME

On the opposite side of the edifice, other scientists are replicating the process with muscle cells. Like the fat filaments, the lean musculus cells volition exist transferred to big bioreactors—temperature- and pressure-controlled steel vessels—where, bathed in a nutrient broth optimized for cell multiplication, they will continue to grow. Once they terminate the proliferation stage, the fat and the muscle tissue will be sieved out of their split vats and reunited into a product resembling ground hamburger meat, with the verbal same genetic code every bit the cows in Farmer John's pasture. (The farmer has asked to go by his starting time proper name only, in lodge to protect his cows, and his farm, from too much media attention.)

That last product, identical to the ground beefiness you lot are used to buying in the grocery shop in every manner simply for the fact that it was grown in a reactor instead of coming from a butchered cow, is the effect of years of research, and could help solve one of the biggest conundrums of our era: how to feed a growing global population without increasing the greenhouse-gas emissions that are heating our planet past the point of sustainability. "What we do to cows, it's terrible," says Melke, shaking her head. "What cows exercise to the planet when we subcontract them for meat? It'south fifty-fifty worse. Only people desire to eat meat. This is how nosotros solve the problem."

Once stem cells are isolated from the biopsy and fed a nutrient-dense growth medium, they thicken into filaments of fatty. Once mature, they can be composite with cultivated muscle cells to create a product similar to ground beef.

Ricardo Cases for TIME

When it comes to the importance of fat in the final product, Melke admits to a slight bias. She is a senior scientist on the Fatty Squad, a small group of specialists within the larger scientific ecosystem of Mosa Meat, the Maastricht-based startup whose founders introduced the get-go hamburger grown from stalk cells to the globe viii years ago. That burger cost $330,000 to produce, and at present Melke's Fatty Team is working with the Muscle Team, the (stalk jail cell) Isolation Team and the Calibration Team, amongst others, to bring what they call cell-cultivated meat to market at an affordable toll.

They are not the only ones. More than 70 other startups effectually the world are courting investors in a race to deliver lab-grown versions of beef, chicken, pork, duck, tuna, foie gras, shrimp, kangaroo and even mouse (for cat treats) to marketplace. Contest is trigger-happy, and few companies have allowed journalists in for fearfulness of risks to intellectual property. Mosa Meat granted TIME exclusive admission to its labs and scientists so the procedure tin can be better understood by the full general public.

Livestock raised for food directly contributes v.8% of the world'south almanac greenhouse-gas emissions, and up to fourteen.5% if feed production, processing and transportation are included, according to the U.N. Nutrient and Agriculture Organization. Industrial animate being agriculture, particularly for beef, drives deforestation, and cows emit methane during digestion and nitrous oxide with their manure, greenhouse gases 25 and 298 times more potent than carbon dioxide, respectively, over a 100-year period.

Read More: Dinner As Nosotros Know it Is Hurting the Planet. But What If We Radically Rethink How We Make Food?

In 2019, the U.N.'southward International Panel on Climate change issued a special report calling for a reduction in global meat consumption. The report found that reducing the apply of fossil fuels alone would not exist plenty to proceed planetary temperature averages from going beyond 1.v°C above preindustrial levels, at which point the floods, droughts and woods fires we are already starting to see will negatively impact agronomics, reducing arable land while driving up costs. Nonetheless global demand for meat is set to virtually double by 2050, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI), as growing economies in developing nations conductor the poor into the meat-eating middle class.

The Mosa squad. From left: Peter Verstrate, co-founder and chief operating officeholder; Maarten Bosch, CEO; Mark Post, primary scientific officer, at their headquarters in Maastricht, Netherlands, in July

Ricardo Cases for TIME

Growing meat in a bioreactor may seem like an expensive overcorrection when just reducing beef intake in high-consuming nations past 1.five hamburgers per calendar week, per person, could reach meaning climate gains, co-ordinate to the WRI. But denying pleasure, even in the pursuit of a global proficient, is rarely an effective way to drive modify. Earlier this year the U.N. published the largest ever opinion poll on climate change, canvassing 1.2 million residents of 50 countries. Most two-thirds of the respondents view the issue as a "global emergency." Nonetheless, few favored found-based diets equally a solution. "For l years, climate activists, global health experts and animal-welfare groups take been begging people to swallow less meat, but per capita consumption is higher than ever," says Bruce Friedrich, head of the Skillful Nutrient Plant, a nonprofit organization promoting meat alternatives. The reason? It tastes too good, he says. "Our bodies are programmed to crave the dense calories. Unfortunately, current production methods are devastating for our climate and biodiversity, and so it's a steep price we're paying for these cravings." The best solution, says Friedrich, is meat alternatives that cost the same or less, and taste the same or meliorate. Melke and her fellow scientists at Mosa say they are getting very close.

According to Marking Postal service, the Dutch scientist who midwifed the first lab-grown hamburger into existence, and who co-founded Mosa Meat in 2015, one one-half-gram biopsy of cow musculus could in theory create up to iv.4 billion lb. of beefiness—more than what Mexico consumes in a year. For the moment, however, Mosa Meat is aiming for 15,000 lb., or 80,000 hamburgers, per biopsy. Even by those modest metrics, Farmer John's footling herd could supply about 10% of kingdom of the netherlands' annual beef consumption. Eventually, says Mail, nosotros would need only some 30,000 to 40,000 cows worldwide, instead of the 300 meg nosotros slaughter every year, without the environmental and moral consequences of large-scale intensive cattle farming. "I admire vegetarians and vegans who are disciplined enough to take activity on their principles," says Post. "But I can't give up meat, and most people are like me. So I wanted to make the choice for those people easier, to be able to keep on eating meat without all the negative externalities."

Even equally it sets out to modify everything about meat product, cellular agriculture, as the nascent industry is called, will in theory change nada nigh meat consumption. This presents a tantalizing opportunity for investors, who have thrown nearly $1 billion at cultivated-meat companies over the past six years. Participating in the high-contour stampede to invest in the industry: Bill Gates, Richard Branson, Warren Buffett and Leonardo DiCaprio. Plant-based burger companies such as Impossible and Beyond already paved the way past proving that the market place wants meat alternatives. Cellular agriculture promises to up that game, providing the exact aforementioned experience equally meat, not a pea-poly peptide facsimile.

While individual investment has been vital for getting the industry off the ground, it is not enough given the immense benefits that the technology could provide the world were it adult at large calibration, says Friedrich of the Good Nutrient Institute. Cultivated-meat product could accept as much impact on the climate crisis as solar power and wind energy, he argues. "Just like renewable energy and electrical vehicles have been successful considering of government policies, we need the same government support for cultivated meat."

Read More than: How Mainland china Could Change the World by Taking Meat Off the Menu

In the concurrently, regulatory approval helps. In December 2020, GOOD Meat, the cultivated-meat division of California-based food-technology company Eat Just Inc., was granted regulatory approving to sell its chicken product to the public in Singapore, a global first. Subsequently that month, a tasting eating place for cell-based chicken produced past Israeli startup SuperMeat opened in State of israel. Cultivated meat could be a $25 billion global industry by 2030, bookkeeping for as much as 0.5% of the global meat supply, according to a new report from consulting firm McKinsey & Co. But to go there, many technological, economic and social hurdles must be tackled before cultivated cutlets fully replace their predecessors on supermarket shelves.

When Austrian food-trends analyst Hanni Rützler appeared onstage to sense of taste Mark Postal service's burger at its public debut in London, on Aug. 5, 2013, her biggest fear was that it might gustatory modality and then bad she would spit information technology out on the live video broadcast. Merely once the burger started sizzling in the pan and the familiar aroma of browning meat hitting her nose, she relaxed. "It was closer to the original than I even expected," she says. At the tasting, she pronounced it "close to meat, only not that juicy." That was to be expected, says Mosa co-founder, COO and food technologist Peter Verstrate—the burger was 100% lean meat. And without fat, burgers don't work. In fact, without fat, he says, yous'd be hard-pressed to tell the difference between a piece of beef and a cut of lamb. Fat isn't necessarily harder to create than muscle. It'southward simply that as with poly peptide cells, getting the process right is time-consuming, and Verstrate and Post prioritized protein. The technology itself is relatively straightforward and has been used for years in the pharmaceutical manufacture to manufacture insulin from pig pancreases: identify and isolate the stem cells—the chameleon-like building blocks of animal biology—prod them to create the desired tissue, and then encourage them to proliferate past feeding them a cell-culture medium made upwards of amino acids, sugars, salts, lipids and growth factors. Scientists have been trying for years to apply the same process to grow artificial organs, arteries and blood vessels, with mixed results.

Post, a vascular cardiologist, used to be 1 of those scientists. He jokes that stem-cell meat, unlike organs, doesn't have to function. On the other hand, it has to be produced in massive amounts at a reasonable cost, and pharmaceutical companies have spent decades and billions of dollars attempting—and largely failing—to scale up stalk-jail cell production to a fraction of what it would have to make cultivated meat affordable. If cellular-agronomics companies succeed where so many others have failed, it could unlock a completely new manner of feeding human beings, as radical a transformation every bit the shift from hunting to domesticating animals was thousands of years ago. Despite investor enthusiasm, that's nonetheless a big if; Eat Only, the company closest to market place, is producing simply a couple hundred pounds of cultivated chicken a year.

Read More: I Tried Lab-Grown Fish Maw. Here's Why It Could Assistance Salve Our Oceans

Many of the scientists at Mosa reflexively attribute sentience to the cells they are working with, discussing their likes and dislikes as they would those of a family pet. Fat tissue can handle temperature swings and rough handling; muscle is more sensitive and needs exercise. "Information technology'southward like producing cows on a really microscopic calibration," says Laura Jackisch, the head of the Fat Squad. "We basically desire to make the cells every bit comfy equally possible." That means fine-tuning their cell-civilisation medium in the same way you lot would regulate a moo-cow's feed to maximize growth and wellness. For ane biopsy to reach the 4.iv billion lb. of meat in Postal service's theoretical scenario, it would accept to double 50 times. So far, Jackisch's team has fabricated it to the mid-20s.

Laura Jackisch in forepart of the analytics lab, where Mosa measures the safety of products.

Ricardo Cases for TIME

A lot of that has to do with the quality of the growth medium. Until recently, most cultivated-meat companies used a prison cell civilisation derived from fetal bovine serum (FBS), a pharmaceutical-manufacture staple that comes from the blood of calf fetuses, inappreciably a viable ingredient for a production that is supposed to cease animal slaughter. The serum is as expensive as it is controversial, and Jackisch and her fellow scientists spent most of the past year developing a plant-based culling. They have identified what, exactly, the cells need to thrive, and how to reproduce information technology in big amounts using plant products and proteins derived from yeast and bacteria. "What we have done is pretty breathtaking," she says. "Figuring out how to brand a replacement [for FBS] that'due south also affordable means that nosotros tin can actually sell this product to the masses." In May, the Fat Team fried up a couple of teaspoons. Though they could tell from the cell structure and lipid profile that they had created a almost identical production, they were still astonished by the taste. "It was so intense, a rich, bulky, compact flavor," says Jackisch, a vegan of vi years. "It was an instant flashback to the days when I used to eat meat. I started peckish steak again." She about picked up a couple on her way abode from the lab that night.

For all the successes that cultivated-meat companies have broadcast over the past few years, biotechnologist Ricardo San Martin, research director for the UC Berkeley Alternative Meats Lab, is skeptical that lab-bench triumphs will translate into mass-market sales anytime soon, if at all. Not ane of the companies currently courtship investment has proved it tin manufacture products at scale, he says. "They bring in all the investors and say, 'Here is our chicken.' And yes, information technology is really chicken, considering there are chicken cells. Only not very many. And not enough for a marketplace."

The skepticism is justified—very few people outside of Israel and Singapore have actually been able to try cultivated meat. (Citing a pending Due east.U. regulatory filing, Mosa declined to allow TIME endeavor its burger. Eat But offered a tasting but would not allow access to its labs.) And the rollout of Consume Just's chicken nuggets in Singapore raises as many questions as information technology answers. At the moment, the cost to produce cultivated meat hovers around $50 a pound, co-ordinate to Michael Dent, a senior technology analyst at marketplace-research company IDTechEx. Eat Just's three-asset portion costs about $17, or 10 times equally much as the local McDonald'southward equivalent. CEO Josh Tetrick admits that the visitor is losing "a lot" on every sale, simply argues that the current production cost per pound "is but not relevant." At this signal, says Dent, making a profit isn't the signal. "It is non in itself a viable product. Simply it's been very, very successful at getting people talking about cultured meat. And it'south been very successful in getting [Eat] Simply some other round of investments."

Read More: Why Nosotros Must Revolutionize Food Systems to Salve Our Planet

On Sept. 20, Eat Just announced that its Practiced Meat division had secured $97 million in new funding, adding to an initial $170 million publicized in May. The company besides recently announced that it was partnering with the government of Qatar to build the first ever cultivated-meat facility in the Middle Due east outside of Israel. In June, Tetrick confirmed that the company, which also produces institute-based egg and mayonnaise products, was mulling a public listing in late 2021 or early 2022, with a possible $3 billion valuation. But all that investment still isn't enough to scale the production process to profitability, let alone to make a dent in the conventional meat industry, says Tetrick. "Y'all tin make the prettiest steak in the globe in the lab, just if you can't make this stuff at large scale, it doesn't matter."

The biggest obstacle to getting the price per pound of cell-cultivated meat below that of chicken, beefiness or pork, says Tetrick, is the physical equipment. GOOD Meat is currently using 1,200- and five,000-liter bio-reactors, enough to produce a few hundred pounds of meat at a time. To go large scale, which Tetrick identifies as "somewhere n of ten one thousand thousand lb. per facility per year, where my mom could buy information technology at Walmart and my dad could pick it up at a fast-food chain," would require 100,000-liter bioreactors, which currently do not exist. Vessels that big, he says, are an engineering challenge that may take as long every bit five years to solve. GOOD Meat has never been able to examination the capacity of cell proliferation to that extent, just Tetrick is convinced that once he has the necessary bioreactors, it will exist a slam dunk.

San Martin, at UC Berkeley, says Tetrick's confidence clashes with the basics of cellular biology. Perpetual cell segmentation may work with yeasts and bacteria, but mammalian cells are entirely different. "At a certain point, yous enter the realm of physical limitations. As they grow they excrete waste. The viscosity increases to a point where you cannot get enough oxygen in and they end upwards suffocating in their ain poo." The but mode San Martin could see cellular agronomics working on the kind of scale Tetrick is talking about is if there were a breakthrough with genetic technology. "But I don't know anyone who's gonna eat a burger made out of genetically modified lab-grown cells," he says. Mosa Meat, based in the GMO-phobic E.U., has admittedly ruled out genetic modification, and Tetrick says his current products don't apply GMOs either.

That said, his rush to market has led him to rely on technologies that become against the company'south slaughter-gratuitous (or cruelty-free) ethos. Not long later the visitor'due south cultivated chicken asset was released for sale in Singapore, Tetrick revealed that FBS had been used in the production process, even though he concedes that it is "self-manifestly antithetical to the idea of making meat without needing to harm a life." The company has since adult an FBS-free version, but it is not even so in utilize, awaiting regulatory review.

Eat Just'due south initial bait and switch left a bad gustatory modality, says Paring. Cell-cultured meat engineering science may be sound, but if consumers start having doubts nigh the production and what's in information technology, at that place could be a backfire confronting the industry as a whole, particularly if FBS continues to be used. "The first products are what everybody will judge the whole industry on," says Dent. He points to the botched rollout of genetically modified seeds in the 1990s as a precedent. "Despite the science pointing to GMOs being a safer, more reliable option for agronomics, they're still [a] pariah. Information technology could get the same way with cultured meat. If they get it wrong now, in twenty years, people will still be proverb, 'Cultured meats, uh-uh, freak meats, we aren't touching information technology.'"

For the moment, Mosa is focused on re-creating ground beef instead of whole cuts. A ground product is easier, and cheaper, to make—the fat and muscle come out of the bioreactor as an unstructured mass, already fit for blending. Other companies, similar Israel's Aleph Farms, take opted to go straight for the holy grail of the cellular-agronomics world—a well-marbled steak—by 3-D printing the stem cells onto a collagen scaffold, the same process medical scientists are now using to abound artificial organs. So far, Aleph has only managed to produce thin strips of lean meat, and while the technology is promising, a market-ready rib eye is notwithstanding years away.

Pocket-sized sparse slabs are exactly what Michael Selden, co-founder and CEO of the Berkeley-based startup Finless Foods, which is producing cell-cultivated tuna, wants. Few people would pay $fifty for a pound of cultivated beef—fifteen times the toll of the conventional version—but consumers are already paying more for high-grade sushi. "Bluefin tuna sells in restaurants for $x to $20 for ii pieces of sashimi. That's $200 a pound," he says. Sashimi, with its thin, repeatable strips and regular fatty striations, is much easier to create than a thick marbled steak, and Selden says Finless Foods has already produced something "close to perfect." His cell-cultivated bluefin tuna is nearly identical to the original in terms of diet and taste profile, he says, simply the texture nonetheless needs work. "It's just a little chip crunchier than we want it to be." But he's confident that by the time the product makes it through the regulatory process—he's hoping past the end of the year or early 2022—his team will have perfected the texture. If they do, it could be the first cultivated meat production on the U.S. market.

Cell-cultivated luxury products could be the ideal thin cease of the wedge for the market, attracting conscientious—and well-heeled—consumers who want an environmentally friendly product, and thus creating space for the technological advances that will bring downward the cost of article meat alternatives similar cultivated beef and chicken. "People who are buying upstanding nutrient correct now are doing the correct thing, but the vast majority of people are never going to convert" when it'due south but about doing the right matter, says Selden. "So we desire to brand stuff that competes non on morals or ideals—although it holds those values—but competes on gustatory modality, toll, nutrition and availability." Assuming they can, it will revolutionize the meat business.

"If I was in the beef industry, I would be shaking in my boots, because there's no style that conventionally grown beefiness is going to exist able to compete with what'due south coming," says Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. There are many reasons people eat meat, ranging from the taste to religious and cultural traditions. But the bulk of meat consumption is non cultural, says Verstrate of Mosa Meat. "It'due south only your average McDonald's every day. And if for that type of consumption, if you lot can present an culling that is non only similar but the same, without all those downsides that traditional meat has, so it simply makes no sense to impale animals anymore."

Read More: How Eating Less Meat Could Help Protect the Planet From Climatic change

4 of the world's v largest meat companies (JBS, Cargill, Tyson and BRF) are already embracing the engineering. From a market betoken of view, information technology makes sense, says Friedrich of the Good Food Institute. "These companies want to feed high-quality protein to equally many people as possible, as profitably as possible. That is their entire business model. If they can brand meat from plants that satisfies consumers, if they can cultivate meat from cells that tastes the same and costs less, they will shift."

A transition to a lab-grown meat source doesn't necessarily mean the end of all cows, just the stop of factory farming. Basis beefiness makes upward half the retail beef market in the U.S., and most of it comes from the industrial feedlots that pose the greatest environmental threats. Eliminating commodity meat, along with its ugly labor issues, elevated risks of zoonotic affliction spread and animal-welfare concerns, would become a long way toward reining in the outsize impact of animal-meat production on the planet, says Friedrich. "The meat that people eat considering information technology is cheap and convenient is what needs to be replaced. Merely in that location volition ever exist the Alice Waterses of the world—and there are lots of them—who will happily pay more for ethically ranched meat from live animals."

Small herds like Farmer John's could provide both. John feeds his cows on pasture for most of the year—rather than on cattle feed, which is typically more environmentally intensive—and rotates them through his orchards in order to supplement the soil with their manure, a natural fertilizer. When he needs to feed them in the winter, he uses leftover hay from his wheat and barley crops. Information technology'due south a form of regenerative agronomics that is impossible to replicate on the large scale that industrial meat production requires to overcome its smaller margins. "Nosotros desire proficient nutrient for everybody. But if nosotros do this [the old] way, we only have good food for some people," John says. That'south why he's willing to embrace the new technology, fifty-fifty if information technology is a threat to his way of life. "This is the future, and I'yard proud that my cows are function of it."

Information technology'southward likely to be more than a year earlier John can finally gustation the lab-grown version of meat from his cows. Mosa is in the process of applying for regulatory approval from the E.U. In the meantime, the company is already expanding into a new space with roughly 100,000 liters of bioreactor capacity, enough to produce several tons of meat every six to 8 weeks. Richard McGeown, the chef who cooked Mail's offset burger on the live circulate, is already dreaming about how he will melt and serve the next i at his eating house in southern England. He'd like to pair it with an anile cheddar, smoky ketchup and house-made pickles. "Information technology would do swell," he says. "Anybody loves a expert burger." More important, he'd beloved to serve something that is every bit good for the environment every bit it is good to eat.

Josias Mouafo stands in front of a CNC (calculator numerical control) motorcar which makes custom made parts for Mosa's processes.

Ricardo Cases for TIME

Simply for those in the $386 billion-a-year cow business organisation, a boxing is brewing. As production moves from feedlot to mill, cattle ranchers stand to lose both jobs and investments. Similar coal land in the era of make clean free energy, entire communities are at risk of existence left behind, and they volition fight. "The cattle industry will do everything they can to telephone call lab-grown meat into question," says Leiserowitz. "Because in one case it breaks through to grocery stores, they're competing on basic stuff, similar taste and price. And they know they won't exist able to win."

The U.S. Cattlemen's Association has already petitioned the U.S. Section of Agriculture to limit the use of the terms beef and meat exclusively to "products derived from the mankind of a [bovine] fauna, harvested in the traditional style." A decision is awaiting, simply if it comes down in the favor of the cattle industry, it could create a meaning barrier to market adoption of cell-cultured meat, says Dent. "For a new product that consumers don't know and don't trust, the terms you can use brand a critical difference. Who'southward going to purchase something called 'lab-grown cell-protein isolates'?"

"It's meat," says Tetrick. "Even down to the genetic level, it is meat. Information technology'due south only made in a different way." Tetrick, who won a similar naming battle in 2015 when his company, then known equally Hampton Creek, successfully maintained the right to call its eggless mayonnaise substitute Just Mayo, says the U.Due south. Cattlemen'south Clan's complaint is equally senseless as if the U.S. automotive industry had argued that Tesla couldn't utilise the give-and-take car to describe its electric vehicles, on the ground that they lacked an internal combustion engine. Even so, he says, naming is critically important. As the applied science has gathered speed over the past several years, terms including cell-cultured, cultivated, slaughter-free, prison cell-based, clean, lab-grown and synthetic accept been variously used, simply consensus is gathering around cultivated meat, which is Tetrick's term of option.

Verstrate, at Mosa, is ambivalent. "Ultimately we're going to produce a hamburger that is delicious. We tin can telephone call it meat or we tin can call it Joe, but if a meat lover consumes it and has the same feel every bit when consuming a peachy Wagyu burger, then nosotros're good to go."

Source: https://time.com/6109450/sustainable-lab-grown-mosa-meat/

0 Response to "Does Cows With a Gentic Defect Make Th Beef Taste Bad?"

Postar um comentário